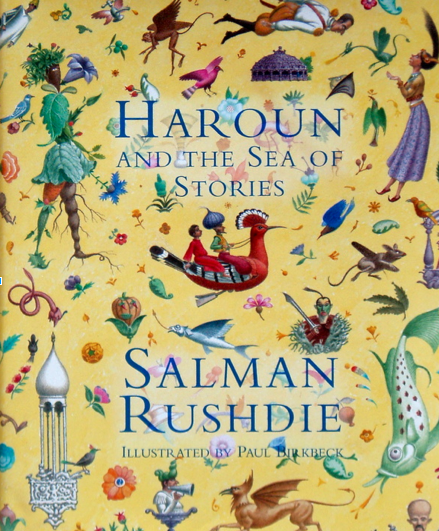

Although Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories seems to be nothing more than a fascinating children’s story that follows the adventures of a little boy in a fantasy world, it also serves to protest against censorship.

After writing The Satanic Verses in 1988, Rushdie was accused of being irreverent to Islam, and was banned in the Muslim world for being blasphemous. In 1989, a fatwa was ordered on him by Ayatollah Khomeini, the spiritual leader of Iran at the time; a price was placed on his head, and his execution was ordered. Forced to hide in the United Kingdom for protection under the course of several years, Haroun and the Sea of Stories not only reflects events in his life following the fatwa, but it also comments on the problems existing in India today. However, at the heart of the story, the book is meant for children.

“Haroun is a tale. Even to call it a parable is too much. It must have, as they say, no designs upon it. Zafar will not read it to advance the public good, or even to comfort his father. He must read it for fun,” Rushdie said.

At first, Haroun and the Sea of Stories began as an oral tale that Rushdie told his son, Zafar, during bath time, since he promised him to write a book for children, instead of one for adults. However, following the fatwa, Rushdie was forced to leave his family to go into hiding. Accordingly, the book focuses on the relationship between a father and a son.

Beginning in “a city so ruinously sad that it had forgotten its name,” Haroun Khalifa lives with his mom and dad, Rashid, who is a famous storyteller. Soon, his mother leaves the family to run off with Mr. Sengupta, and Haroun lashes out against his dad for his useless stories. In an attempt to resolve the situation, Rashid takes Haroun on one of his jobs to speak for a politician, but finds that he has lost his abilities to weave a tale. After meeting a water genie name Iff, Haroun wrangles a deal with him to restore his father’s abilities through drinking water from the Sea of Stories. However, he fails, while also discovering that someone named Khattum-Shud (which means silence) is poisoning the water. Haroun then decides to go with Iff to Kahani, Earth’s second moon, and help stop Khattum-Shud and cure his father.

Although the tale is targeted towards children, it has underlying messages that are meant for an older audience, and can be read by people of all ages. The book is delightfully entertaining, and the characters are humorous and enjoyable, reacting to different events in a childlike, exaggerated manner. Besides its political messages, the book also alludes to Alice in Wonderland and the Wizard of Oz.

Throughout his journey, Haroun meets eccentric and lovable characters, such as Mr. Butt, the bus driver turned mechanical bird, and Prince Bolo, who blindly loves the ugly Princess Batcheat (“that nose, those teeth”), and Blabbermouth, who pretends to be a boy in order to join the army of Gup. In the meantime, he has to face the Chupwala army, lead by Khattam-Shud.

Either way, Haroun and the Sea of Stories can be read for anybody who is looking for something lighthearted and fun to read, or those who are willing to dig deeper into the messages that Rushdie sends to his audience about the balance of censorship, the negatives of war, and the necessities of storytelling and words.